Species of Thailand

Northern goshawk

Accipiter gentilis

Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

In Thai: เหยี่ยวนกเขาท้องขาว

The northern goshawk (; Accipiter gentilis) is a medium-large raptor in the family Accipitridae, which also includes other extant diurnal raptors, such as eagles, buzzards and harriers. As a species in the genus Accipiter, the goshawk is often considered a "true hawk". The scientific name is Latin; Accipiter is "hawk", from accipere, "to grasp", and gentilis is "noble" or "gentle" because in the Middle Ages only the nobility were permitted to fly goshawks for falconry.

This species was first described under its current scientific name by Linnaeus in his Systema naturae in 1758.

It is a widespread species that inhabits many of the temperate parts of the Northern Hemisphere. The northern goshawk is the only species in the genus Accipiter found in both Eurasia and North America. It may have the second widest distribution of any true member of the family Accipitridae, behind arguably only the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), which has a broader range to the south of Asia than the goshawk. The only other acciptrid species to also range in both North America and Eurasia according to current opinion, is the more Arctic-restricted rough-legged buzzard (Buteo lagopus). Except in a small portion of southern Asia, it is the only species of "goshawk" in its range and it is thus often referred to, both officially and unofficially, as simply the "goshawk". It is mainly resident, but birds from colder regions migrate south for the winter. In North America, migratory goshawks are often seen migrating south along mountain ridge tops at nearly any time of the fall depending on latitude.

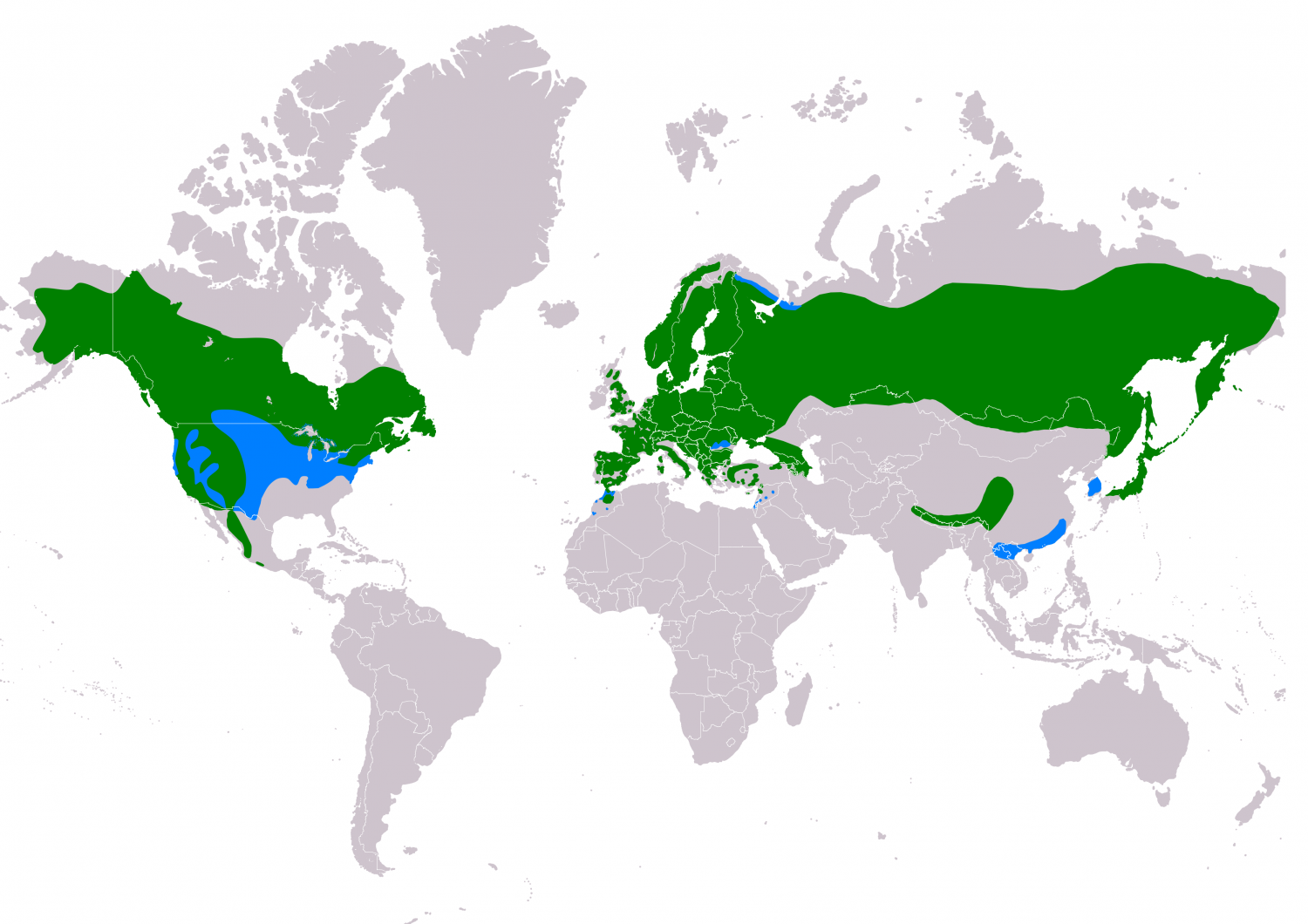

Distribution

The northern goshawk has a large circumpolar distribution. In Eurasia, it is found in most areas of Europe excluding Ireland and Iceland. It has a fairly spotty distribution in western Europe (e.g. Great Britain, Spain, France) but is more or less found continuously through the rest of the continent. Their Eurasian distribution sweeps continuously across most of Russia, excluding the fully treeless tundra in the northern stretches, to the western limits of Siberia as far as Anadyr and Kamchatka. In the Eastern Hemisphere, they are found in their southern limits in extreme northwestern Morocco, Corsica and Sardinia, the "toe" of Italy, southern Greece, Turkey, the Caucasus, Sinkiang's Tien Shan, in some parts of Tibet and the Himalayas, western China and Japan. In winter, northern goshawks may be found rarely as far south as Taif in Saudi Arabia and perhaps Tonkin, Vietnam.

In North America, they are most broadly found in the western United States, including Alaska, and western Canada. Their breeding range in the western contiguous United States largely consists of the wooded foothills of the Rocky Mountains and many other large mountain ranges from Washington to southern California extending east to central Colorado and westernmost Texas. Somewhat discontinuous breeding populations are found in southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, thence also somewhat spottily into western Mexico down through Sonora and Chihuahua along the Sierra Madre Occidental as far as Jalisco and Guerrero, their worldwide southern limit as a breeding species.

The goshawk continues east through much of Canada as a native species, but is rarer in most of the eastern United States, especially the Midwest where they are not typically found outside the Great Lakes region, where a good-sized breeding population occurs in the northern parts of Minnesota, Illinois, Michigan and somewhat into Ohio; a very small population persists in the extreme northeast corner of North Dakota. They breed also in mountainous areas of New England, New York, central Pennsylvania and northwestern New Jersey, sporadically down to extreme northwestern Maryland and northeastern West Virginia. Vagrants have been reported in Ireland, North Africa (central Morocco, northern Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt); the Arabian Peninsula (Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia), southwest Asia (southern Iran, Pakistan), western India (Gujarat) and on Izu-shoto (south of Japan) and the Commander Islands, and in most of the parts of the United States where they do not breed.

Habitat

Northern goshawks can be found in both deciduous and coniferous forests. While the species might show strong regional preferences for certain trees, they seem to have no strong overall preferences nor even a preference between deciduous or coniferous trees despite claims to the contrary. More important than the type of trees are the composition of a given tree stand, which should be tall, old-growth with intermediate to heavy canopy coverage (often more than 40%) and minimal density undergrowth, both of which are favorable for hunting conditions. Also, goshawks typically require close proximity to openings in which to execute additional hunting. More so than in North America, the goshawks of Eurasia, especially central Europe, may live in fairly urbanized patchworks of small woods, shelter-belts and copses and even use largely isolated trees in central parts of Eurasian cities. Access to waterways and riparian zones of any kind is not uncommon in goshawk home ranges but seems to not be a requirement. Narrow tree-lined riparian zones in otherwise relatively open habitats can provide suitable wintering habitat in the absence of more extensive woodlands. The northern goshawk can be found at almost any altitude, but recently is typically found at high elevations due to a paucity of extensive forests remaining in lowlands across much of its range. Altitudinally, goshawks may live anywhere up to a given mountain range's tree line, which is usually 3000 m ft abbr=on in elevation or less. The northern limit of their distribution also coincides with the tree line and here may adapt to dwarf tree communities, often along drainages of the lower tundra. In winter months, the northernmost or high mountain populations move down to warmer forests with lower elevations, often continuing to avoid detection except while migrating. A majority of goshawks around the world remain sedentary throughout the year.

Description

The northern goshawk has relatively short, broad wings and a long tail, typical for Accipiter species and common to raptors that require maneuverability within forest habitats. For an Accipiter, it has a relatively sizeable bill, relatively long wings, a relatively short tail, robust and fairly short legs and particularly thick toes. Across most of the species' range, it is blue-grey above or brownish-grey with dark barring or streaking over a grey or white base color below, but Asian subspecies in particular range from nearly white overall to nearly black above. Goshawks tend to show clinal variation in color, with most goshawks further north being paler and those in warmer areas being darker but individuals can be either dark in the north or pale in the south. Individuals that live a long life may gradually become paler as they age, manifesting in mottling and a lightening of the back from a darker shade to a bluer pale color. Its plumage is more variable than that of the Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus), which is probably due to higher genetic variability in the larger goshawk. The juvenile northern goshawk is usually a solid to mildly streaky brown above, with many variations in underside color from nearly pure white to almost entirely overlaid with broad dark cinnamon-brown striping. Both juveniles and adults have a barred tail, with 3 to 5 dark brown or black bars. Adults always have a white eye stripe or supercilia, which tends to be broader in northern Eurasian and North American birds. In North America, juveniles have pale-yellow eyes, and adults develop dark red eyes usually after their second year, although nutrition and genetics may affect eye color as well. In Europe and Asia, juveniles also have pale-yellow eyes while adults typically develop orange-colored eyes, though some may have only brighter yellow or occasionally ochre or brownish eye color. Moulting starts between late March and late May, the male tends to moult later and faster than the female. Moulting results in the female being especially likely to have a gap in its wing feathers while incubating and this may cause some risk, especially if the male is lost, as it inhibits her hunting abilities and may hamper her defensive capabilities, putting both herself and the nestlings in potential danger of predation. The moult takes a total of 4–6 months, with tail feathers following the wings then lastly the contour and body feathers, which may not be completely moulted even as late as October.

Although existing wing size and body mass measurements indicate that the Henst's goshawk (Accipiter henstii) and Meyer's goshawk (Accipiter meyerianus) broadly overlap in size with this species, the northern goshawk is on average the largest member of the genus Accipiter, especially outsizing its tropic cousins in the larger Eurasian races. The northern goshawk, like all Accipiters, exhibits sexual dimorphism, where females are significantly larger than males, with the dimorphism notably greater in most parts of Eurasia. Linearly, males average about 8% smaller in North America and 13% smaller than females in Eurasia, but in the latter landmass can range up to a very noticeable 28% difference in extreme cases. Male northern goshawks are 46 to 61 cm in abbr=on long and have a 89 to 105 cm in abbr=on wingspan. The female is much larger, 58 to 69 cm in abbr=on long with a 108 to 127 cm in abbr=on wingspan. In a study of North American goshawks (A. g. atricapillus), males were found to average 56 cm in abbr=on in total length, against females which averaged 61 cm in abbr=on. Males from six subspecies average around 762 g lb abbr=on in body mass, with a range from all races of 357 to 1200 g lb abbr=on. The female can be up to more than twice as heavy, averaging from the same races 1150 g lb abbr=on with an overall range of 758 to 2200 g lb abbr=on. Among standard measurements, the most oft-measured is wing chord which can range from 286 to 354 mm in abbr=on in males and from 324 to 390 mm in abbr=on in females. Additional, the tail is 200 - 295 mm in abbr=on, the culmen is 20 - 26.3 mm in abbr=on and the tarsus is 68 - 90 mm in abbr=on.

Voice

Northern goshawks normally only vocalize during courtship or the nesting season. Adult goshawks may chatter a repeated note, varying in speed and volume based on the context. When calling from a perch, birds often turn their heads slowly from side to side, producing a ventriloquial effect. The male calls a fast, high-pitched kew-kew-kew when delivering food or else a very different croaking guck or chup. The latter sound has been considered by some authors similar to that of a person snapping the tongue away from the roof the mouth; the males produce it by holding the beak wide open, thrusting the head up and forward, than bringing it down as the sound is emitted, repeated at intervals of five seconds. This call is uttered when the male encounters a female. Two calls have been recorded mainly from brooding females in the race A. g. atricapillus: a recognition scream of short, intense notes (whee-o or hee-ya) which ends in harsh, falsetto tone; then a dismissal call given when the male lingers after delivering food, consisting of a choked, cut-off scream. Meanwhile, the adult female's rapid strident kek-kek-kek expresses alarm or intent to mob towards threatening intruders. This is often done when mobbing a predator such as a great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) and as it progresses the female's voice may lower slightly in pitch and becomes harsh and rasping. As the intensity of her attacks increases, her kakking becomes more rapid and can attain a constant screaming quality. Females often withdraw into the treetops when fatigued, and their calls are then spaced at longer intervals. Males respond to interlopers or predators with a quieter, slower gek gek gek or ep ep ep. A call consisting of kek…kek.kekk kek kek-kek-kek is used mainly by females in advertisement and during pre-laying mutual calling. Both sexes also may engage in kakking during copulation. Vocalizations mainly peak in late courtship/early nesting around late March to April, can begin up to 45 minutes before sunrise, and are more than twice in as frequent in the first three hours of daylight as in the rest of the day. Occasionally hunting northern goshawks may make shrill screams when pursuing prey, especially if a lengthy chase is undertaken and the prey is already aware of its intended predator.

Taxonomy

The genus Accipiter contains nearly 50 known living species and is the most diverse genus of diurnal raptors in the world. This group of agile, smallish, forest-dwelling hawks has been in existence for possibly tens of millions of years, probably as an adaptation to the explosive numbers of small birds that began to occupy the world's forest in the last few eras. The harriers are the only group of extant diurnal raptors that seem to bear remotely close relation to this genus, whereas buteonines, Old World kites, sea eagles and chanting-goshawks are much more distantly related and all other modern accipitrids are not directly related.

Within the genus Accipiter, the northern goshawk seems to belong to a superspecies with other larger goshawks from different portions of the world. Meyer's goshawk, found in the South Pacific, has been posited as the most likely to be most close related living cousin to the northern goshawk, the somewhat puzzling gap in their respective ranges explained by other Palearctic raptors such as Bonelli's eagles (Aquila fasciata) and short-toed eagles (Circaetus gallicus) that have extant isolated tropical island populations and were probably part of the same southwest Pacific radiation that led to the Meyer's goshawk. A presumably older radiation of this group occurred in Africa, where it led to both the Henst's goshawk of Madagascar and the black sparrowhawk (Accipiter melanoleucus) of the mainland. While the Henst's goshawk quite resembles the northern goshawks, the black sparrowhawk is superficially described as a “sparrowhawk” due to its relatively much longer and finer legs than those of typical goshawks but overall its size and plumage (especially that of juveniles) is much more goshawk than sparrowhawk-like.

Outside of the presumed superspecies, the genus Erythrotriorchis may be part of an Australasian radiation of basal goshawks based largely on their similar morphology to northern goshawks. Genetic studies have indicated that the Cooper's hawk of North America is also fairly closely related to the northern goshawk, having been present in North America before either of the other two North American Accipiters. However, the much smaller sharp-shinned hawk, which has similar plumage to the Cooper's hawk and seems to be most closely related to the Eurasian sparrowhawk, appears to have occupied North America the latest of the three North American species, despite having the broadest current distribution of any Accipiter in the Americas (extending down through much of South America).

The term goshawk comes from the Old English gōsheafoc, "goose-hawk".

Subspecies

The northern goshawk appears to have diversified in northern, central Eurasia and spread both westwards to occupy Europe and, later on, eastwards to spread into North America across the Bering Land Bridge. Fossil remains show that goshawks were present in California by the Pleistocene era. Two non-exclusive processes could have occurred to cause the notably color and size variation of northern goshawks throughout its range: isolation in the past enabled gene combinations to assort as distinct morphs that suited conditions in different geographical areas, followed by a remixing of these genotypes to result in clines, or subtle variation in modern selection pressures led to a diversity of hues and patterns. As a result of the high variation of individual goshawks in plumage characteristics and typical trends in clinal variation and size variations that largely follow Bergmann's rule and Gloger's rule, an excessive number of subspecies have been described for the northern goshawk in the past. In Europe (including European Russia) alone, 12 subspecies were described between 1758 and 1990. Most modern authorities agree on listing nine to ten subspecies of northern goshawks from throughout its range.

- A. g. gentilis (Linnaeus, 1758) – The nominate race is distributed through most of the species current European range, excluding northern Fennoscandia, northwestern Russia and possibly some of the Mediterranean islands they inhabit. Outside of Europe, this subspecies' range extends south to northwestern Africa (almost entirely Morocco) and east in Eurasia to Urals, the Caucasus and Asia Minor. It is a typically large subspecies, with high levels of sexual dimorphism. The wing chord of males ranges from 300 to 342 mm in abbr=on and of females from 336 to 385 mm in abbr=on. Body mass is variable, range from 517 to 1110 g lb abbr=on in males and from 820 to 2200 g lb abbr=on in females. In some cases, the largest adult females (including some exceptionally big females which are the heaviest goshawks known from anywhere) from within a population are up to four times heavier than the smallest adult males, although this is exceptional. The highest average weights come from central Fennoscandia, where the sexes weigh on average 865 g lb abbr=on and 1414 g lb abbr=on, respectively. The lowest come from Spain, where goshawks of this race weigh a median of 690 g lb abbr=on in males and 1050 g lb abbr=on in females. The nominate race is generally a dark slaty-brown color on its back and wing coverts with a blackish-brown head. The supercilium is thin and the underside is generally creamy with heavy dark barring. On average, in addition to their smaller size, nominate goshawks to the south of the race's distribution have thinner supericilia and broader and denser barring on the underside. An aberrant “isabelline” morph is known mainly from central and eastern Europe, where the goshawk may be a general beige color (somewhat similar to the pale birds from the races albidus and buteoides), but such birds appear to be very rare.

- A. g. arrigonii (Kleinschmidt, 1903) – This is an island race found on the Mediterranean isles of Sardinia and Corsica. It averages smaller and weaker-footed than goshawks from the nominate race. The wing chord measures 293 to 308 mm in abbr=on in males and 335 to 347 mm in abbr=on in females. This race is typically a more blackish brown above with almost fully black head, while the underside is almost pure white and more heavily overlaid with black barring and conspicuous black shaft-streaks. This subspecies is not listed by all authorities but is often considered valid.

- A. g. buteoides (Menzbier, 1882) – This race is characteristic of the northern stretches of the western Eurasian range of goshawks, being found as a breeding species from northern Fennoscandia to western Siberia, ranging as far as the Lena River. In the eastern portion of its distribution, many birds may travel south to central Asia to winter. This is a large race, averaging larger than most populations of the nominate race but being about the same size as the big nominate goshawks with which they may overlap and interbreed with in Fennoscandia. The wing chord in males ranges from 308 to 345 mm in abbr=on while that of females ranges from 340 to 388 mm in abbr=on. The body mass of males has been reported from 870 to 1170 g lb abbr=on, with an average of 1016 g lb abbr=on, while that of females is reportedly 1190 to 1850 g lb abbr=on, with an average of 1355 g lb abbr=on. Usually, this race is an altogether paler colour than the nominate, being blue-grey above with a dusky-grey crown and a broad supercilium. The underside is white with rather fine blackish-brown barring. Pale flecking on the feather shafts sometimes result in barred appearance on the contour feathers of the nape, back and upper wing. Many birds from this subspecies also have a tan to pale brown eye color. These two characteristics are sometimes considered typical of this race, but individuals are rather variable. In western Siberia, about 10% of birds of this race are nearly pure white (similar to albidus) with varied indications of darker streaking.

- A. g. albidus (Menzbier, 1882) – This race of goshawk is found in northeastern Siberia and Kamchatka. Many birds of this race travel south for the winter to Transbaikalia, northern Mongolia and Ussuriland. This race continues the trend for goshawks to grow mildly larger eastbound in Eurasia and may be the largest known race based on the midpoint of known measurements of this race, although limited sample sizes of measured goshawks shows they broadly overlap in size with A. g. buteoides and large-bodied populations of A. g. gentilis. The wing chord can range from 316 to 346 mm in abbr=on in males and from 370 to 388 mm in abbr=on in females. Known males have scaled from 894 to 1200 g lb abbr=on while a small sample of females weighed have had a body mass between 1300 and 1750 g lb abbr=on. This is easily the palest race of northern goshawk. Many birds are pale grey above with much white about the head and very sparse barring below. However, about half of the goshawks of this race are more or less pure white, with at most only a few remnants of pale caramel flecking about the back or faint brownish markings elsewhere.

- A. g. schvedowi (Menzbier, 1882) – This race ranges from the Urals east to the Amurland, Ussuriland, Manchuria, west-central China and sporadically as a breeder into Sakhalin and the Kuril islands. A. g. schvedowi averages smaller than the other races on the mainland of Eurasia, with seemingly the highest sexual dimorphism of any goshawk race, possibly as an adaptation to prey partitioning in the exceptionally sparse wooded fringes of the desert-like steppe habitat that characterizes this race's range. The wing chord has been found to measure 298 to 323 mm in abbr=on in males and 330 to 362 mm in abbr=on in females. Body mass of 15 males was found to be merely 357 to 600 g lb abbr=on with a mean of 501 g lb abbr=on, the lowest adult weights known for this species, while two adult females scaled 1000 and 1170 g lb abbr=on, respectively, or more than twice as much on average. Beyond its smaller size, its wings are reportedly relatively shorter and feet relatively smaller and weaker than other Eurasian races. In color, this race is typically a slate-grey above with a blackish head and is densely marked below with thin brown barring.

- A. g. fujiyamae (Swann & Hartert, 1923) – Found through the species' range in Japan, from the islands of Hokkaido south to the large island of Honshu, in the latter down to as far south as forests a bit north of Hiroshima. A fairly small subspecies, it may average slightly smaller than A. g. schvedowi linearly, but it is less sexually dimorphic in size and weighs slightly more on average. The wing chord is the smallest known from any race, 286 to 300 mm in abbr=on in males and 302 to 350 mm in abbr=on in females. However, the weights of 22 males ranged from 602 to 848 g lb abbr=on, averaging 715 g lb abbr=on while 22 females ranged from 929 to 1265 g lb abbr=on, averaging 1098 g lb abbr=on. The coloration of this race is not dissimilar from A. g. schvedowi, but is still darker slate above and they tend to have heavier barring below, probably being the darkest race on average, rivaled only by the similar insular race from the opposite side of the Pacific, A. g. laingi.

- A. g. atricapillus (Wilson, 1812) – Sometimes simply referred to as the American goshawk. This subspecies occupies a majority of the species' range in North America, excluding some islands of the Pacific Northwest and the southern part of the American Southwest. American goshawks are generally slightly smaller on average than most Eurasian ones, although there are regional differences in size that confirm mildly to Bergmann's rule within this race. Furthermore, sexual dimorphism in size is notably less pronounced in American goshawks than in most Eurasian races. Overall, the wing chord is 308 to 337 mm in abbr=on in males and 324 to 359 mm in abbr=on in females. Size within atricapillus based on body mass seems to be highest in interior Alaska, followed by the Great Lakes, is intermediate in the northwest United States from eastern Washington to the Dakotas as well as in southeast Alaska thence decreasing mildly along the Pacific in Oregon and California and smallest of all within the race in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau states (i.e. Nevada, Utah and northern and central Arizona). Conspicuously, wing size did not correspond to variations in body mass and more southerly goshawks were frequently longer winged than the more massive northerly ones. Male atricapillus goshawk have been found to weigh from 655 to 1200 g lb abbr=on and females from 758 to 1562 g lb abbr=on. The lightest reported mean weights were from goshawks in northern and central Arizona, weighing a mean of 680 g lb abbr=on in males and 935 g lb abbr=on while the highest were from a small sample of Alaskan goshawks which weighed some 905 g lb abbr=on in males and 1190 g lb abbr=on in females. Almost identical mean weights for goshawks as in Alaska were recorded for goshawks from Alberta as well. This race is typically a blue-gray color above with a boldly contrasting black head and broad white supercilia. American goshawks are often grayish below with fine gray waving barring and, compared to most Eurasian goshawks, rather apparent black shaft streaks which in combination create a vermiculated effect that is all-together messier looking than in most Eurasian birds. From a distance, atricapillus can easily appear solidly all-gray from the front. Due to this, the adult goshawk in America is sometimes called the “gray ghost”, a name also somewhat more commonly used for adult male hen harriers. Birds from mainland Alaska tend to be paler overall with more pale flecking than other American goshawks.

- A. g. laingi (Tavernier, 1940) – This insular race is found on the Queen Charlotte Islands and Vancouver Island. This subspecies is slightly smaller than the goshawks found on the mainland and is linearly the smallest race on average in North America. The wing chord of males can range from 312 to 325 mm in abbr=on and that of females is 332 to 360 mm in abbr=on and is on average nearly 5% smaller than those sampled goshawks from the nearby mainland. These goshawks are characteristically darker than mainland goshawks with the black of the crown extending to the interscapulars. The underside is a sootier gray overall.

- A. g. apache (van Rossem, 1938) – The range of this subspecies extends from southern Arizona and New Mexico down throughout the species' range in Mexico. This subspecies has the longest median wing size of any race, running contrary to Bergmann's rule that northern birds should outsize southern ones in widely distributed temperate species. In males the wing chord ranges from 344 to 354 mm in abbr=on while in females it ranges from 365 to 390 mm in abbr=on. However, in terms of body mass, it is only slightly heavier than the goshawks found discontinuously somewhat to the north in the Great Basin and the Colorado Plateau and lighter than the heaviest known American goshawks from Alaska, Alberta and Wisconsin despite exceeding the goshawks from these areas in wing size. The weight of 49 males ranged from 631 to 744 g lb abbr=on, averaging 704 g lb abbr=on, while that of 88 females from two studies ranged from 845 to 1265 g lb abbr=on, averaging 1006 g lb abbr=on. Aside from its overall larger size, apache reportedly averages larger in foot size than most other American goshawks. Birds of this race tend to be darker than other American goshawks aside from the laingi type birds. Due to its shortage of distinct features beyond proportions, this is considered one of the more weakly separated among current separate subspecies, with some authors considering it merely a clinal variation of atricapillus. Even the greater wing size in southern birds follows a trend for the wing chord to increase in size in the south on the contrary to body mass.

Similar species

The juvenile plumage of the species may cause some confusion, especially with other Accipiter juveniles. Unlike other northern Accipiters, the adult northern goshawk never has a rusty color to its underside barring. In Eurasia, the smaller male goshawk is sometimes confused with a female sparrowhawk, but is still notably larger, much bulkier and has relatively longer wings, which are more pointed and less boxy. Sparrowhawks tend to fly in a frequently flapping, fluttering type flight. Wing beats of northern goshawks are deeper, more deliberate, and on average slower than those of the Eurasian sparrowhawk or the two other North American Accipiters. The classic Accipiter flight is a characteristic "flap flap, glide", but the goshawk, with its greater wing area, can sometimes be seen steadily soaring in migration (smaller Accipiters almost always need to flap to stay aloft). In North America juveniles are sometimes confused with the smaller Cooper's hawk (Accipiter cooperii), especially between small male goshawks and large female Cooper's hawks. Unlike in Europe with sparrowhawks, Cooper's hawks can have a largish appearance and juveniles may be regularly mistaken for the usually less locally numerous goshawk. However, the juvenile goshawk displays a heavier, vertical streaking pattern on chest and abdomen, with the juvenile Cooper's hawk streaking frequently (but not always) in a “teardrop” pattern wherein the streaking appears to taper at the top, as opposed to the more even streaking of the goshawk. The goshawk sometimes seems to have a shorter tail relative to its much broader body. Although there appears to be a size overlap between small male goshawks and large female Cooper's hawks, morphometric measurements (wing and tail length) of both species demonstrate no such overlap, although weight overlap can rarely occur due to variation in seasonal condition and food intake at time of weighing. Rarely, in the southern stretches of its Asian wintering range, the northern goshawk may live alongside the crested goshawk (Accipiter trivirgatus) which is smaller (roughly Cooper's hawk-sized) and has a slight crest as well as a distinct mixture of denser streaks and bars below and no supercilia.

Northern goshawks are sometimes mistaken for species even outside of the genus Accipiter especially as juveniles of each respective species. In North America, four species of buteonine hawk (all four of which are smaller than goshawks to a certain degree) may be confused with them on occasion despite the differing proportions of these hawks, which all have longer wings and shorter tails relative to their size. A species so similar it is sometimes nicknamed the “Mexican goshawk”, gray hawk (Buteo plagiatus) juveniles (overlapping with true goshawks in the southwest United States into Mexico) have contrasting face pattern with bold dusky eye-stripes, dark eyes, barred thighs and a bold white “U” on the uppertail coverts. The roadside hawk (Rupornis magnirostris) (rarely in same range in Mexico) is noticeably smaller with paddle-shaped wings, barred lower breast and a buff “U” on undertail coverts in young birds. Somewhat less likely to confuse despite their broader extent of overlap are the red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus) which have a narrow white-barred, dark-looking tail, bold white crescents on their primaries and dark wing edges and the broad-winged hawk (Buteo playpterus) which also has dark wing edges and a differing tapered wing shape. Even wintering gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus) juveniles have been mistaken for goshawks and vice versa on occasion, especially when observed distantly perched. However, the bulkier, broader headed yet relatively shorter tailed falcon still has many tell-tale falcon characteristics like pointed, longer wings, a brown malar stripe as well as its more extensive barring both above and below.

Territoriality

The northern goshawk is always found solitarily or in pairs. This species is highly territorial as are most raptorial birds, maintaining regularly spaced home ranges that constitute their territory. Territories are maintained by adults in display flights. During nesting, the home ranges of goshawk pairs are from 600 to 4000 ha acre abbr=on and these vicinities tend to be vigorously defended both to maintain rights to their nests and mates as well as the ranges’ prey base. During display flight goshawks may engage in single or mutual high-circling. Each sex tends to defend the territory from others of their own sex. Territorial flights may occur almost through the year, but peak from January to April. Such flights may include slow-flapping with exaggerated high deep beats interspersed with long glides and undulations. In general, territorial fights are resolved without physical contact, often with one (usually a younger bird seeking a territory) retreats while the other approaches in a harrier-like warning flight, flashing its white underside at the intruder. If the incoming goshawk does not leave the vicinity, the defending goshawk may increase the exaggerated quality of its flight including a mildly undulating wave-formed rowing flight and the rowing flight with its neck held in a heron-like S to elevate the head and maximally expose the pale breast as a territorial threat display. Territorial skirmishes may on occasion escalate to physical fights in which mortalities may occur. In actual fights, goshawks fall grappling to the ground as they attempt to strike each other with talons.

Migration

Although at times considered rather sedentary for a northern raptor species, the northern goshawk is a partial migrant. Migratory movements generally occur between September and November (occasionally extending throughout December) in the fall and February to April in the spring. Spring migration is less extensive and more poorly known than fall migration, but seems to peak late March to early April. Some birds up to as far north as northern Canada and central Scandinavia may remain on territory throughout the winter. Northern goshawks from northern Fennoscandia have been recorded traveling up to 1640 km mi abbr=on away from first banding but adults seldom are recorded more than 300 km mi abbr=on from their summer range. In Sweden, young birds distributed an average of 377 km mi abbr=on in the north to an average of 70 km mi abbr=on in the south. In northern Sweden, young generally disperse somewhat south, whereas in south and central Sweden, they typically distributed to the south (but not usually across the 5-km Kattegat straits). On the other hand, 4.3% of the southern Swedish goshawks actually moved north. Migrating goshawks seem to avoid crossing water, but sparrowhawks seems to be able to do so more regularly. In central Europe, few birds travel more than 30 km mi abbr=on throughout the year, a few juveniles have exceptionally been recorded traveling up to 300 km mi abbr=on. In Eurasia, very small numbers of migratory northern goshawks cross the Strait of Gibraltar and Bosporus in autumn but further east more significant winter range expansions may extend from northern Iran & southern Turkmenia to Aral & Balkhash lakes, from Kashmir to Assam, extreme northwestern Thailand, northern Vietnam, southern China, Taiwan, Ryukyu Islands and South Korea. Migratory goshawks in North America may move down to Baja California, Sinaloa and into most of west Texas, but generally in non-irruptive years, goshawks winter no further south than Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina. Some periodic eruptions to nearly as far as the Gulf of Mexico have been recorded at no fewer than 10 years apart. In one case, a female that was banded in Wisconsin was recovered 1860 km mi abbr=on in Louisiana, a first ever record of the species in that state.

Prey availability may primarily dictate the proportion of goshawk populations that migrate and the selection of wintering areas, followed by the presence of snow which may aid prey capture in the short-term but in the long-term is likely to cause higher goshawk mortality. Showing the high variability of migratory movements, in one study of winter movements of adult female goshawks that bred in high-elevation forests of Utah, about 36% migrated 100 to 613 km mi abbr=on to the general south, 22% migrated farther than that distance, 8.3% migrated less far, 2.7% went north instead of south and 31% stayed throughout winter on their breeding territory. Irruptive movements seem to occur for northern populations, i.e. those of the boreal forests in North America, Scandinavia, and possibly Siberia, with more equal sex ratio of movement and a strong southward tendency of movements in years where prey such as hares and grouse crash. Male young goshawks tend to disperse farther than females, which is unusual in birds, including raptors. It has been speculated that larger female juveniles displace male juveniles, forcing them to disperse farther, to the incidental benefit of the species’ genetic diversity. In Cedar Grove, Wisconsin, there were more than twice as many juvenile males than females recorded migrating. At the hawk watch at Cape May Point State Park in New Jersey, few adult males and no adult females have been recorded in fall migration apart from irruptive years, indicating that migration is more important to juveniles. More juveniles were recorded migrating than adults in several years of study from Sweden. In northern Accipiters including the goshawk, there seems to be multiple peaks in numbers of migrants, an observation that suggests partial segregation by age and sex.

Hunting behavior

As typical of the genus Accipiter (as well as unrelated forest-dwelling raptors of various lineages), the northern goshawk has relatively short wings and a long tail which make it ideally adapted to engaging in brief but agile and twisting hunting flights through dense vegetation of wooded environments. This species is a powerful hunter, taking birds and mammals in a variety of woodland habitats, often utilizing a combination of speed and obstructing cover to ambush their victims. Goshawks often forage in adjoining habitat types, such as the edge of a forest and meadow. Hunting habitat can be variable, as in a comparison of habitats used in England found that only 8% of landscapes used were woodlands whereas in Sweden 73-76% of the habitat used was woodland, albeit normally within 200 m ft abbr=on of an opening. In North America, goshawks are generally rather more likely than those from Eurasia to hunt within the confines of mature forest, excluding areas where prey numbers are larger outside of the forest, such as where scrub-dwelling cottontails are profuse. One study from central Sweden found that locally goshawks typically hunt within the largest patches of mature forests, selecting second growth forest less than half as often as its prevalence in the local environment. The northern goshawk is typically considered a perch-hunter. Hunting efforts are punctuated by a series of quick flights low to the ground, interspersed with brief periods of scanning for unsuspecting prey from elevated perches (short duration sit-and-wait predatory movements). These flights are meant to be inconspicuous, averaging about 83 seconds in males and 94 seconds in females, and prey pursuits may be abandoned if the victims become aware of the goshawk too quickly. More sporadically, northern goshawks may watch from prey from a high soar or gliding flight above the canopy. One study in Germany found an exceptional 80% of hunting efforts to be done from a high soar but the author admitted that he was probably biased by the conspicuousness of this method. In comparison, a study from Great Britain found that 95% of hunting efforts were from perches. A strong bias for pigeons as prey and a largely urbanized environment in Germany explains the local prevalence of hunting from a soaring flight, as the urban environment provides ample thermals and obstructing tall buildings which are ideal for hunting pigeons on the wing.

Northern goshawks rarely vary from their perch-hunting style that typifies the initial part of their hunt but seems to be able to show nearly endless variation to the concluding pursuit. Hunting goshawks seem to not only utilize thick vegetation to block them from view for their prey (as typical of Accipiters) but, while hunting flying birds, they seem to be able to adjust their flight level so the prey is unable to see its hunter past their own tails. Once a prey item is selected, a short tail-chase may occur. The northern goshawk is capable of considerable, sustained, horizontal speed in pursuit of prey with speeds of 38 mph kph abbr=on reported. While pursuing prey, northern goshawks has been described both “reckless” and “fearless”, able to pursue their prey through nearly any conditions. There are various times goshawks have been observed going on foot to pursue prey, at times running without hesitation (in a crow-like, but more hurried gait) into dense thickets and brambles (especially in pursuit of galliforms trying to escape), as well as into water (i.e. usually waterfowl). Anecdotal cases have been reported when goshawks have pursue domestic prey into barns and even houses. Prey pursuits may become rather prolonged depending upon the goshawk's determination and hunger, ranging up to 15 minutes while harrying a terrified, agile squirrel or hare, and occasional pair hunting may benefit goshawks going after agile prey. As is recorded in many accipitrids, hunting in pairs (or “tandem hunting”) normally consist of a breeding pair, with one bird flying conspicuously to distract the prey, while the other swoops in from behind to ambush the victim. When gliding down from a perch to capture prey, a goshawk may not even beat its wings, rendering its flight nearly silent. Prey is killed by driving the talons into the quarry and squeezing while the head is held back to avoid flailing limbs, frequently followed by a kneading action until the prey stops struggling. Kills are normally consumed on the ground by juvenile or non-breeding goshawks (more rarely an elevated perch or old nest) or taken to a low perch by breeding goshawks. Habitual perches are used for dismantling prey especially in the breeding season, often called “plucking perches”, which may be fallen logs, bent-over trees, stumps or rocks and can see years of usage. Northern goshawks often leave larger portions of their prey uneaten than other raptors, with limbs, many feathers and fur and other body parts strewn near kill sites and plucking perches, and are helpful to distinguish their kills from other raptors such as large owls, who usually eat everything. The daily food requirements of a single goshawks are around 120 to 150 g oz abbr=on and most kills can feed a goshawk for 1 to 3 days. Northern goshawks sometimes cache prey on tree branches or wedged in a crotch between branches for up to 32 hours. This is done primarily during the nestling stage. Hunting success rates have been very roughly estimated at 15–30%, within average range for a bird of prey, but may be reported as higher elsewhere. One study claimed hunting success rates for pursuing rabbits was 60% and corvids was 63.8%.

Prey spectrum

Northern goshawks are usually opportunistic predators, as are most birds of prey. The most important prey species are small to medium-sized mammals and medium to large-sized birds found in forest, edge and scrub habitats. Primary prey selection varies considerably not just at the regional but also the individual level as the primary food species can be dramatically different in nests just a few kilometers apart. As is typical in various birds of prey, small prey tends to be underrepresented in prey remains below habitual perches and nests (as only present in skeletal remains within pellets) whereas pellets underrepresent large prey (which is usually dismantled away from the nest) and so a combined study of both remains and pellets is recommended to get a full picture of goshawks’ diets. Prey selection also varies by season and a majority of dietary studies are conducted within the breeding season, leaving a possibility of bias for male-selected prey, whereas recent advanced in radio-tagging have allowed a broader picture of goshawk's fairly different winter diet (without needing to kill goshawks to examine their stomach contents). Northern goshawks have a varied diet that has reportedly included over 500 species from across its range, and at times their prey spectrum can extend to nearly any available kind of bird or mammal except the particularly large varieties as well as atypical prey including reptiles and amphibians, fish and insects. However, a few prey families dominate the diet in most parts of the range, namely corvids, pigeons, grouse, pheasants, thrushes and woodpeckers (in roughly descending order of importance) among birds and squirrels (mainly tree squirrels but also ground squirrels especially in North America) and rabbits and hares among mammals.

Birds are usually the primary prey in Europe, constituting 76.5% of the diet in 17 studies. In North America, by comparison, they constitute 47.8% in 33 studies and mammals account for a nearly equal portion of the diet and in some areas rather dominate the food spectrum. Studies have shown that from several parts of the Eurasian continent from Spain to the Ural mountains mammals contributed only about 9% of the breeding season diet. However, mammals may be slightly underrepresented in Eurasian data because of the little-studied presence of mammals as a food source in winter, particularly in the western and southern portions of Europe where the lack of snowfall can allow large numbers of rabbits. Staple prey for northern goshawks usually weighs between 50 and 2000 g oz abbr=on, with average prey weights per individual studies typically between 215 and 770 g oz abbr=on. There is some difference in size and type between the prey caught by males and larger females. Prey selection between sexes is more disparate in the more highly dimorphic races from Eurasia than those from North America. In the Netherlands, male prey averaged 277 g oz abbr=on whereas female prey averaged 505 g oz abbr=on, thus a rough 45% difference . In comparison, the average prey caught by each sex in Arizona was 281.5 g oz abbr=on and 380.4 g oz abbr=on, respectively, or around a 26% difference. Northern goshawks often select young prey during spring and summer, attacking both nestling and fledgling birds and infant and yearling mammals, as such prey is often easiest to catch and convenient to bring to the nest. In general, goshawks in Fennoscandia, shift their prey selection to when the birds produce their young: first waterfowl, then quickly to corvids and thrushes and then lastly to grouse, even though adults are also freely caught opportunistically for all these prey types. This is fairly different from Vendsyssel, Denmark, where mostly adult birds were caught except for thrushes and corvids, as in these two groups, the goshawks caught mostly fledglings.

Corvids

Overall, one prey family that is known to be taken in nearly every part of the goshawk's range is the corvids, although they do not necessarily dominate the diet in all areas. Some 24 species have been reported in the diet. The second most commonly reported prey species in breeding season dietary studies from both Europe and North America are both large jays, the 160 g oz abbr=on Eurasian jay (Glarius glandarius) and the 128 g oz abbr=on Steller's jay (Cyanocitta stelleri). These species were recorded in studies from northeastern Poland and the Apennines of Italy (where the Eurasian jays made up a quarter of the food by number) and in northwestern Oregon and the Kaibab Plateau of Arizona (where the Steller's made up 37% by number) as the main prey species by number. The conspicuously loud vocalizations, somewhat sluggish flight (when hunting adult or post-fledging individuals) and moderate size of these jays make them ideal for prey-gathering male goshawks. Another medium-sized corvid, the 218 g oz abbr=on Eurasian magpie (Pica pica) is also amongst the most widely reported secondary prey species for goshawks there. Magpies, like large jays, are rather slow fliers and can be handily outpaced by a pursuing goshawk. Some authors claim that taking of large corvids is a rare behavior, due of their intelligence and complex sociality which in turn impart formidable group defenses and mobbing capabilities. One estimation claimed this to be done by about 1–2% of adult goshawks during the breeding season (based largely on studies from Sweden and England), however, on the contrary many goshawks do routinely hunt crows and similar species. In fact, there are some recorded cases where goshawks were able to exploit such mobbing behavior in order to trick crows into close range, where the mob victim suddenly turned to grab one predaceously. In the following areas Corvus species were the leading prey by number: the 440 g oz abbr=on hooded crow (Corvus cornix) in the Ural mountains (9% by number), the 245 g oz abbr=on western jackdaw (Corvus monedula) in Sierra de Guadarrama, Spain (36.4% by number), the 453 g lb abbr=on rook (Corvus frugilegus) in the Zhambyl district, Kazakhstan (36.6% by number) and the 457 g lb abbr=on American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) in New York and Pennsylvania (44.8% by number). Despite evidence that northern goshawks avoid nesting near common ravens (Corvus corax), the largest widespread corvid (about the same size as a goshawk at 1040 g lb abbr=on) and a formidable opponent even one-on-one, they are even known to prey on ravens seldomly. Corvids taken have ranged in size from the 72 g oz abbr=on Canada jay (Perisoreus canadensis) to the raven.

Pigeons and doves

In Europe, the leading prey species numerically (the main prey species in 41% of 32 European studies largely focused on the nesting season) is the 352 g oz abbr=on rock pigeon (Columba livia). Although the predominance of rock pigeons in urban environments that host goshawks such as the German cities of Hamburg (where they constituted 36% by number and nearly 45% by weight of the local diet) or Cologne is predictable, evidence shows that these development-clinging pigeons are sought out even within ample conserved woodland from Portugal to Georgia. In areas where goshawk restrict their hunting forays to field and forest, they often catch another numerous pigeon, the 490 g lb abbr=on common wood pigeon (Columba palumbus) (the largest pigeon the goshawk naturally encounters and is known to hunt). The latter species was the main prey in the diet of northern goshawks from in the Dutch-German border (37.7% of 4125 prey items) and Wales (25.1% by number and 30.5% by biomass of total prey). It has been theorized that male goshawks in peri-urban regions may be better suited with their higher agility to ambushing rock pigeons in and amongst various manmade structures whereas females may be better suited due the higher overall speeds to taking out common wood-pigeons, as these typically forage in wood-cloaked but relatively open fields; however males are efficient predators of common wood-pigeons as well. Studies have proven that, while hunting rock pigeons, goshawks quite often select the oddly colored pigeons out of flocks as prey, whether the plumage of the flock is predominantly dark or light hued, they disproportionately often select individuals of the other color. This preference is apparently more pronounced in older, experienced goshawks and there is some evidence that the males who select oddly-colored pigeons have higher average productivity during breeding. Around eight additional species of pigeon and dove have turned up in the goshawks diet from throughout the range but only in small numbers and in most of North America, goshawks take pigeons less commonly than in Eurasia. One exception is in Connecticut where the mourning dove (Zenaida macroura), the smallest known pigeon or dove the goshawk has hunted at 119 g oz abbr=on, was the second most numerous prey species.

Gamebirds

The northern goshawk is in some parts of its range considered a specialized predator of gamebirds, particularly grouse. All told 33 species of this order have turned up in their diet, including most of the species either native to or introduced in North America and Europe. Numerically, only in the well-studied taiga habitats of Scandinavia, Canada and Alaska and some areas of the eastern United States do grouse typically take a dominant position. Elsewhere in the range, gamebirds are often secondary in number but often remain one of the most important contributors of prey biomass to nests. With their general ground-dwelling habits, gamebirds tend to be fairly easy for goshawks to overtake if they remain unseen and, if made aware of the goshawk, the prey chooses to run rather than fly. If frightened too soon, gamebirds may take flight and may be chased for some time, although the capture rates are reduced considerably when this occurs. Pre-fledgling chicks of gamebirds are particularly vulnerable due to the fact that they can only run when being pursued. In several parts of Scandinavia, forest grouse have historically been important prey for goshawks both in and out of the nesting season, principally the 1080 g lb abbr=on black grouse (Tetrao tetrix) and the 430 g oz abbr=on hazel grouse (Bonasa bonasia) followed in numbers by larger 2950 g lb abbr=on western capercaillies (Tetrao urogallus) and the 570 g lb abbr=on willow ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus) which replace the other species in the lower tundra zone. The impression of goshawks on the populations of this prey is considerable, possibly the most impactful of any predator in northern Europe considering their proficiency as predators and similarity of habitat selection to forest grouse. An estimated 25-26% of adult hazel grouses in Finnish and Swedish populations in a few studies fall victim to goshawks, whereas about 14% of adult black grouse are lost to this predator. Lesser numbers were reportedly culled in one study from northern Finland. However, adult grouse are less important in the breeding season diet than young birds, an estimated 30% of grouse taken by Scandinavian goshawks in summer were neonatal chicks whereas 53% were about fledgling age, the remaining 17% being adult grouse. This is fairly different than in southeastern Alaska, where grouse are similarly as important as in Fennoscandia, as 32.1% of avian prey deliveries were adults, 14.4% were fledglings and 53.5% were nestlings.

Northern goshawks can show somewhat of a trend for females to be taken more so than males while hunting adult gamebirds, due to the larger size and more developed defenses of males (such as leg spurs present for defense and innerspecies conflicts in male of most pheasant species). Some authors have claimed this of male ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus cochilus), but these trends are not reported everywhere, as in southern Sweden equal numbers of adult male and female ring-necked pheasants, both sexes averaging 1135 g lb abbr=on, were taken. While male goshawks can take black and hazel grouse of any age and thence deliver them to nests, they can only take capercaillie of up to adult hen size, averaging some 1800 g lb abbr=on, the cock capercaillie at more than twice as heavy as the hen is too large for a male goshawk to overtake. However, adult female goshawks have been reported attacking and killing cock capercaillie, mainly during winter. These average about 4000 g lb abbr=on in body mass and occasionally may weigh even more when dispatched. Similarly impressive feats of attacks on other particularly large gamebirds have been reported elsewhere in the range, including the 2770 g lb abbr=on Altai snowcock (Tetraogallus altaicus) in Mongolia and, in at least one case, successful predation on an estimated 3900 g lb abbr=on adult-sized young wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) hen in North America (by an immature female goshawk weighing approximately 1050 g lb abbr=on), although taking adults of much larger-bodied prey like this is considered generally rare, the young chicks and poults of such prey species are likely much more often taken. At the other end of the size scale, the smallest gamebird known to be hunted by northern goshawk was the 96 g oz abbr=on common quail. Domestic fowl, particularly chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) are taken occasionally, especially where wild prey populations are depleted. While other raptors are at times blamed for large numbers of attacks on fowl, goshawks are reportedly rather more likely to attack chickens during the day than other raptors and are probably the most habitual avian predator of domestic fowl, at least in the temperate-zone. Particularly large numbers of chickens have been reported in Wigry National Park, Poland (4th most regular prey species and contributing 15.3% of prey weight), Belarus and the Ukraine, being the third most regularly reported prey in the latter two.

In a study of British goshawks, the red grouse (Lagopus lagopus scotica), a race of willow ptarmigan, was found to be the leading prey species (26.2% of prey by number). In La Segarra, Spain, the 528 g lb abbr=on red-legged partridge (Alectoris rufa) is the most commonly reported prey species (just over 18% by number and 24.5% by weight). Despite reports that grouse are less significant as prey to American goshawks, the 560 g lb abbr=on ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) is one of the most important prey species in North America (fourth most reported prey species in 22 studies), having been the leading prey species for goshawks in studies from New York, New Jersey and Connecticut (from 12 to 25% of prey selected) and reported as taken in high numbers elsewhere in several parts of their mutual range. The 1056 g lb abbr=on sooty grouse (Dendragapus fuliginosus) was reported as the leading prey species in southern Alaska (28.4% by number). In the boreal forests of Alberta, grouse are fairly important prey especially in winter.

Squirrels

Among mammalian prey, indisputably the most significant by number are the squirrels. All told, 44 members of the Sciuridae have turned up in their foods. Tree squirrels are the most obviously co-habitants with goshawks and are indeed taken in high numbers. Alongside martens, northern goshawks are perhaps the most efficient temperate-zone predators of tree squirrels. Goshawks are large and powerful enough to overtake even the heaviest tree squirrels unlike smaller Accipiters and have greater agility and endurance in pursuits than do most buteonine hawks, some of which like red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) regularly pursue tree squirrels but have relatively low hunting success rates due to the agility of squirrels. The 296 g oz abbr=on red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) of Eurasia is the most numerous mammalian prey in European studies and the sixth most often recorded prey species there overall. In Oulu, Finland during winter (24.6% by number), in Białowieża Forest, Poland (14.3%), in the Chřiby uplands of the Czech Republic (8.5%) and in Forêt de Bercé, France (12%) the red squirrel was the main prey species for goshawks. In North America, tree squirrels are even more significant as prey, particularly the modestly-sized pine squirrels which are the single most important prey type for American goshawks overall. Particularly the 240 g oz abbr=on American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) is significant, being the primary prey in studies from Minnesota, South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana (in each comprising more than 30% of the diet and present in more than half of known pellets) but also reported everywhere in their foods from the eastern United States to Alaska and Arizona. Much like the American marten (Martes americana), the American distribution of goshawks is largely concurrent with that of American red squirrels, indicating the particular significance of it as a dietary staple. In the Pacific northwest, the 165 g oz abbr=on Douglas squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasii) replaces the red squirrel in both distribution and as the highest contributor to goshawk diets from northern California to British Columbia. The largest occurrence of Douglas squirrel known was from Lake Tahoe, where they constituted 23% of prey by number and 32.9% by weight.

Larger tree squirrels are also taken opportunistically, in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, the 530 g lb abbr=on eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) was the third most significant prey species. Much larger tree squirrels such as western gray squirrels (Sciurus griseus) and fox squirrels (Sciurus niger), both weighing about 800 g lb abbr=on, are taken occasionally in North America. Ground squirrels are also important prey species, mostly in North America, 25 of 44 of squirrel species found in the diet are ground squirrels. Particularly widely reported as a secondary food staple from Oregon, Wyoming, California and Arizona was the 187 g oz abbr=on golden-mantled ground squirrel (Callospermophilus lateralis). In Nevada and Idaho’s Sawtooth National Forest, the 285 g oz abbr=on Belding's ground squirrel (Urocitellus beldingi) fully dominated the food spectrum, comprising up to 74.3% of the prey by number and 84.2% by biomass. Even much bigger ground squirrels such as prairie dogs and marmots are attacked on occasion. Several hoary marmots (Marmota caligala) were brought to nests in southeast Alaska but averaged only 1894 g lb abbr=on, so were young animals about half of the average adult (spring) weight (albeit still considerably heavier than the goshawks who took them). In some cases, adult marmots such as alpine marmots (Marmota marmota), yellow-bellied marmots (Marmota flaviventris) and woodchucks (Marmota monax) have been preyed upon when lighter and weaker in spring, collectively weighing on average about 3500 g lb abbr=on or about three times as much as a female goshawk although are basically half of what these marmots can weigh by fall. About a dozen species of chipmunk are known to be taken by goshawks and the 96 g oz abbr=on eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus) were the second most numerous prey species at nests in central New York and Minnesota. Squirrels taken have ranged in size from the 43 g oz abbr=on least chipmunk (Tamias minimus) to the aforementioned adult marmots.

Hares and rabbits

Northern goshawks can be locally heavy predators of lagomorphs, of which they take at least 15 species as prey. Especially in the Iberian peninsula, the native European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is often delivered to nests and can be the most numerous prey. Even where taken secondarily in numbers in Spain to gamebirds such as in La Segarra, Spain, rabbits tend to be the most significant contributor of biomass to goshawk nests. On average, the weight of rabbits taken in La Segarra was 662 g lb abbr=on (making up 38.4% of the prey biomass there), indicating most of the 333 rabbits taken there were yearlings and about 2-3 times lighter than a prime adult wild rabbit. In England, where the European rabbit is an introduced species, it was the third most numerous prey species at nests. In more snowbound areas where wild and feral rabbits are absent, larger hares may be taken and while perhaps more difficult to subdue than most typical goshawk prey, are a highly nutritious food source. In Finland, females were found to take mountain hare (Lepus timidus) fairly often and they were the second most numerous prey item for goshawks in winter (14.8% by number). In North America, where mammals are more important in the diet, more lagomorphs are taken. In Oregon, snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) are the largest contributor of biomass to goshawks foods (making up to 36.6% of the prey by weight), in eastern Oregon at least 60% of hares taken were adults weighing on average 1500 g lb abbr=on, and in one of three studies from Oregon be the most numerous prey species (second most numerous in the other two). This species was also the second most numerous food species in Alberta throughout the year and the most important prey by weight. Eastern cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus), also averaging some 1500 g lb abbr=on in

This article uses material from Wikipedia released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike Licence 3.0. Eventual photos shown in this page may or may not be from Wikipedia, please see the license details for photos in photo by-lines.

Category / Seasonal Status

Wiki listed status (concerning Thai population): Rare winter visitor

BCST Category: Recorded in an apparently wild state within the last 50 years

BCST Seasonal status: Non-breeding visitor

Scientific classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Accipitriformes

- Family

- Accipitridae

- Genus

- Accipiter

- Species

- Accipiter gentilis

Common names

- Thai: เหยี่ยวนกเขาท้องขาว

Conservation status

Least Concern (IUCN3.1)

Photos

Please help us review the bird photos if wrong ones are used. We can be reached via our contact us page.

Range Map

- Doi Inthanon National Park

- Doi Pha Hom Pok National Park

- Khao Yai National Park

- Mae Rim District, Chiang Mai