Species of Thailand

Common kingfisher

Alcedo atthis

Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

In Thai: นกกะเต็นน้อยธรรมดา

The common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), also known as the Eurasian kingfisher and river kingfisher, is a small kingfisher with seven subspecies recognized within its wide distribution across Eurasia and North Africa. It is resident in much of its range, but migrates from areas where rivers freeze in winter.

This sparrow-sized bird has the typical short-tailed, large-headed kingfisher profile; it has blue upperparts, orange underparts and a long bill. It feeds mainly on fish, caught by diving, and has special visual adaptations to enable it to see prey under water. The glossy white eggs are laid in a nest at the end of a burrow in a riverbank.

Taxonomy

The common kingfisher was first described by Carl Linnaeus in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae in 1758 as Gracula atthis. The modern binomial name derives from the Latin , 'kingfisher' (from Greek , ), and Atthis, a beautiful young woman of Lesbos, and favourite of Sappho.

The genus Alcedo comprises seven small kingfishers that all eat fish as part of their diet. The common kingfisher's closest relative is the cerulean kingfisher that has white underparts and is found in parts of Indonesia.

Description

This species has the typical short-tailed, dumpy-bodied, large-headed, and long-billed kingfisher shape. The adult male of the western European subspecies, A. a. ispida has green-blue upperparts with pale azure-blue back and rump, a rufous patch by the bill base, and a rufous ear-patch. It has a green-blue neck stripe, white neck blaze and throat, rufous underparts, and a black bill with some red at the base. The legs and feet are bright red. It is about 16 cm long with a wingspan of 25 cm, and weighs 34 - 46 g. The female is identical in appearance to the male except that her lower mandible is orange-red with a black tip. The juvenile is similar to the adult, but with duller and greener upperparts and paler underparts. Its bill is black, and the legs are also initially black. Feathers are moulted gradually between July and November with the main flight feathers taking 90–100 days to moult and regrow. Some that moult late may suspend their moult during cold winter weather.

The flight of the kingfisher is fast, direct and usually low over water. The short, rounded wings whirr rapidly, and a bird flying away shows an electric-blue "flash" down its back.

In North Africa, Europe and Asia north of the Himalayas, this is the only small blue kingfisher. In south and southeast Asia, it can be confused with six other small blue-and-rufous kingfishers, but the rufous ear patches distinguish it from all but juvenile blue-eared kingfishers; details of the head pattern may be necessary to differentiate the two species where both occur.

The common kingfisher has no song. The flight call is a short, sharp whistle chee repeated two or three times. Anxious birds emit a harsh, shrit-it-it and nestlings call for food with a churring noise.

Geographical variation

There are seven subspecies differing in the hue of the upperparts and the intensity of the rufous colour of the underparts; size varies across the subspecies by up to 10%. The races resident south of the Wallace Line have the bluest upperparts and partly blue ear-patches.

- A. a. ispida (Linnaeus, 1758). Breeds from Ireland, Spain and southern Norway to Romania and western Russia and winters south to Iraq and southern Portugal.

- A. a. atthis Linnaeus, 1758. Breeds from northwestern Africa and southern Italy east to Afghanistan, Kashmir region, northern Xinjiang, and Siberia; it is a winter visitor south to Israel, northeastern Sudan, Yemen, Oman and Pakistan. Compared to A. a. ispida, it has a greener crown, paler underparts and is slightly larger.

- A. a. bengalensis Gmelin, 1788. Breeds in southern and eastern Asia from India to Indonesia, China, Korea, Japan and eastern Mongolia; winters south to Indonesia and the Philippines. It is smaller and brighter than the European races.

- A. a. taprobana Kleinschmidt, 1894. Resident breeder in Sri Lanka and southern India. Its upperparts are bright blue, not green-blue; it is the same size as A. a. bengalensis.

- A. a. floresiana Sharpe, 1892. Resident breeder from Bali to Timor. Like A. a. taprobana, but the blues are darker and the ear-patch is rufous with a few blue feathers.

- A. a. hispidoides Lesson, 1837. Resident breeder from Sulawesi to New Guinea and the islands of the western Pacific Ocean. Plumage colours are deeper than in A. a. floresiana, the blue on the hind neck and rump is purple-tinged and the ear-patch is blue.

- A. a. solomonensis Rothschild and Hartert, 1905. Resident breeder in the Solomon Islands east to San Cristobal. The largest southeast Asian subspecies, it has a blue ear-patch and is more purple-tinged than A. a. hispidoides, with which it interbreeds.

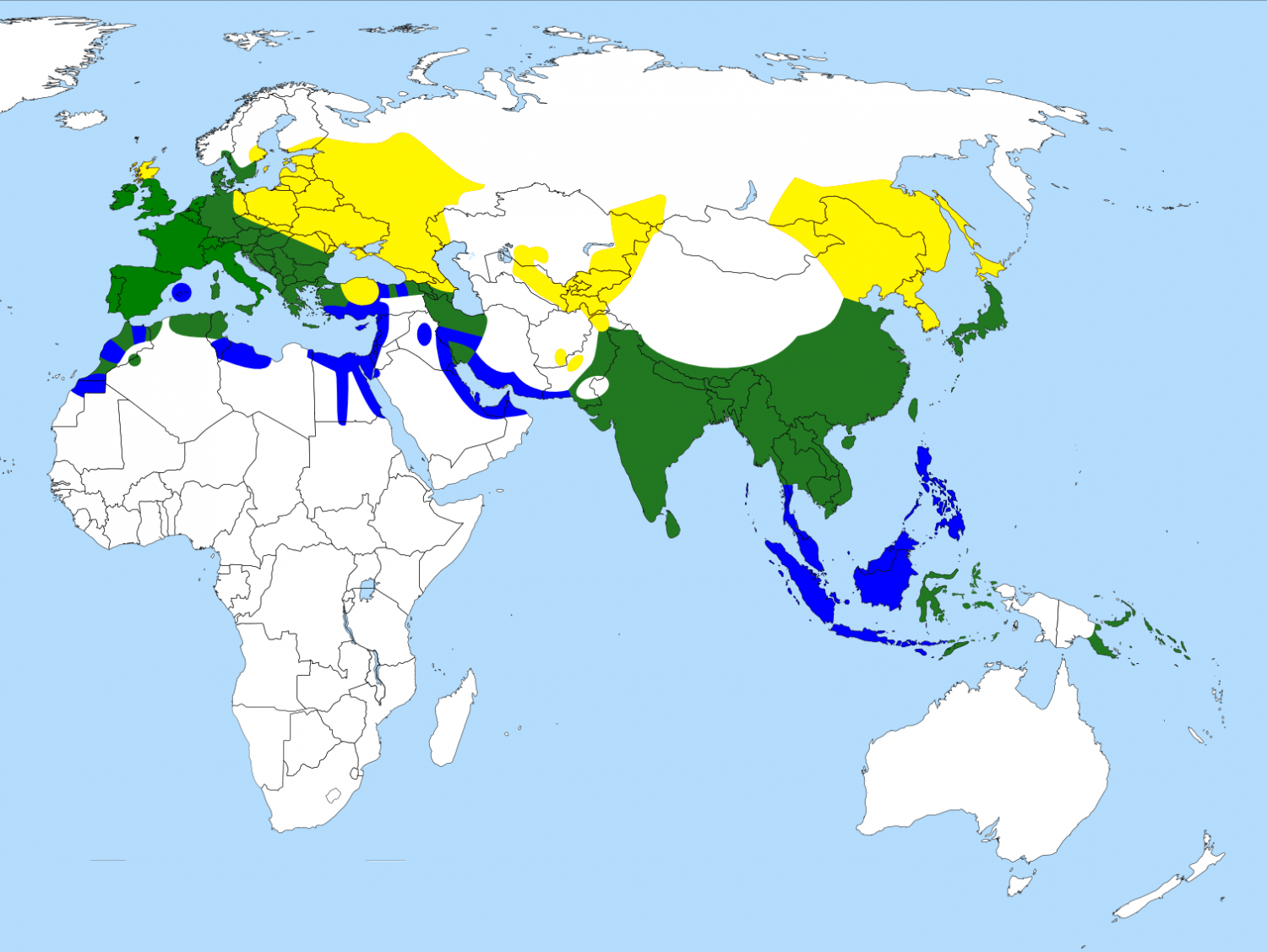

Habitat and distribution

The common kingfisher is widely distributed over Europe, Asia, and North Africa, mainly south of 60°N. It is a common breeding species over much of its vast Eurasian range, but in North Africa it is mainly a winter visitor, although it is a scarce breeding resident in coastal Morocco and Tunisia. In temperate regions, this kingfisher inhabits clear, slow-flowing streams and rivers, and lakes with well-vegetated banks. It frequents scrubs and bushes with overhanging branches close to shallow open water in which it hunts. In winter it is more coastal, often feeding in estuaries or harbours and along rocky seashores. Tropical populations are found by slow-flowing rivers, in mangrove creeks and in swamps.

Common kingfishers are important members of ecosystems and good indicators of freshwater community health. The highest densities of breeding birds are found in habitats with clear water, which permits optimal prey visibility, and trees or shrubs on the banks. These habitats have also the highest quality of water, so the presence of this bird confirms the standard of the water. Measures to improve water flow can disrupt this habitat, and in particular, the replacement of natural banks by artificial confinement greatly reduces the populations of fish, amphibians and aquatic reptiles, and waterside birds are lost. It can tolerate a certain degree of urbanisation, provided the water remains clean.

This species is resident in areas where the climate is mild year-round, but must migrate after breeding from regions with prolonged freezing conditions in winter. Most birds winter within the southern parts of the breeding range, but smaller numbers cross the Mediterranean into Africa or travel over the mountains of Malaysia into Southeast Asia. Kingfishers migrate mainly at night, and some Siberian breeders must travel at least 3000 km between the breeding sites and the wintering areas.

Breeding

Like all kingfishers, the common kingfisher is highly territorial; since it must eat around 60% of its body weight each day, it is essential to have control of a suitable stretch of river. It is solitary for most of the year, roosting alone in heavy cover. If another kingfisher enters its territory, both birds display from perches, and fights may occur, in which a bird will grab the other's beak and try to hold it underwater. Pairs form in the autumn but each bird retains a separate territory, generally at least 1 km long, but up to 3.5 km and territories are not merged until the spring.

The courtship is initiated by the male chasing the female while calling continually, and later by ritual feeding, with copulation usually following.

The nest is in a burrow excavated by both birds of the pair in a low vertical riverbank, or sometimes a quarry or other cutting. The straight, gently inclining burrow is normally 60 – 90 cm long and ends in an enlarged chamber. The nest cavity is unlined but soon accumulates a litter of fish remains and cast pellets.

The common kingfisher typically lays two to ten glossy white eggs, which average 1.9 cm in breadth, 2.2 cm in length, and weigh about 4.3 g, of which 5% is shell. One or two eggs in most clutches fail to hatch because the parent cannot cover them. Both sexes incubate by day, but only the female incubates at night. An incubating bird sits trance-like, facing the tunnel; it invariably casts a pellet, breaking it up with the bill. The eggs hatch in 19–20 days, and the altricial young are in the nest for a further 24–25 days, often more. Once large enough, young birds will come to the burrow entrance to be fed. Two broods, sometimes three, may be reared in a season.

Survival

The early days for fledged juveniles are more hazardous; during its first dives into the water, about four days after leaving the nest, a fledgling may become waterlogged and drown. Many young will not have learned to fish by the time they are driven out of their parents' territory, and only about half survive more than a week or two. Most kingfishers die of cold or lack of food, and a severe winter can kill a high percentage of the birds. Summer floods can destroy nests or make fishing difficult, resulting in starvation of the brood. Only a quarter of the young survive to breed the following year, but this is enough to maintain the population. Likewise, only a quarter of adult birds survive from one breeding season to the next. Very few birds live longer than one breeding season. The oldest bird on record was 21 years.

Other causes of death are cats, rats, collisions with vehicles and windows, and human disturbance of nesting birds, including riverbank works with heavy machinery. Since kingfishers are high up in the food chain, they are vulnerable to build-up of chemicals, and river pollution by industrial and agricultural products excludes the birds from many stretches of otherwise suitable rivers that would be habitats.

This species was killed in Victorian times for stuffing and display in glass cases and use in hat making. English naturalist William Yarrell also reported the country practice of killing a kingfisher and hanging it from a thread in the belief that it would swing to predict the direction in which the wind would blow. Persecution by anglers and to provide feathers for fishing flies were common in earlier decades, but are now largely a thing of the past.

Feeding

The common kingfisher hunts from a perch 1 – 2 m above the water, on a branch, post or riverbank, bill pointing down as it searches for prey. It bobs its head when food is detected to gauge the distance and plunges steeply down to seize its prey usually no deeper than 25 cm below the surface. The wings are opened underwater and the open eyes are protected by the transparent third eyelid. The bird rises beak-first from the surface and flies back to its perch. At the perch the fish is adjusted until it is held near its tail and beaten against the perch several times. Once dead, the fish is positioned lengthways and swallowed head-first. A few times each day, a small greyish pellet of fish bones and other indigestible remains is regurgitated.

The food is mainly fish up to 12.5 cm long, but the average size is 2.3 cm. In Central Europe, 97% of the diet was found to be composed of fish ranging in size from 2 to 10 cm with an average of 6.5 cm (body mass range from <0.1 g to >10 g, average 3 g). Minnows, sticklebacks, small roach and trout are typical prey. About 60% of food items are fish, but this kingfisher also catches aquatic insects such as dragonfly larvae and water beetles, and, in winter, crustaceans including freshwater shrimps. In Central Europe, however, fish represented 99.9% of the diet (data from rivers, streams, and reservoirs from years 1999 to 2013). Common kingfishers have also been observed to catch lamprey. One study found that food provisioning rate increased with brood size, from 1498 g (505 fishes for four nestlings) to 2968 g (894 fishes for eight nestlings). During the fledging period each chick consumed on average 334 g of fish, which resulted in an estimated daily food intake of 37% of the chick's body mass (average over the entire nestling period). The average daily energy intake was 73.5 kJ per chick (i.e., 1837 kJ per 25 days of the fledging period).

A challenge for any diving bird is the change in refraction between air and water. The eyes of many birds have two foveae (the fovea is the area of the retina with the greatest density of light receptors), and a kingfisher can switch from the main central fovea to the auxiliary fovea when it enters water; a retinal streak of high receptor density which connects the two foveae allows the image to swing temporally as the bird drops onto the prey. The egg-shaped lens of the eye points towards the auxiliary fovea, enabling the bird to maintain visual acuity underwater. Because of the positions of the foveae, the kingfisher has monocular vision in air, and binocular vision in water. The underwater vision is not as a sharp as in air, but the ability to judge the distance of moving prey is more important than the sharpness of the image.

Each cone cell of a bird's retina contains an oil droplet that may contain carotenoid pigments. These droplets enhance color vision and reduce glare. Aquatic kingfishers have high numbers of red pigments in their oil droplets; the reason red droplets predominate is not understood, but the droplets may help with the glare or the dispersion of light from particulate matter in the water.

Status

This species has a large range, with an estimated global extent of occurrence of 10 million square kilometres (3.8 million square miles). It has a large population, including an estimated 160, 000–320, 000 individuals in Europe alone. Global population trends have not been quantified, but populations appear to be stable so the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations). For these reasons, the species is evaluated as "least concern".

This article uses material from Wikipedia released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike Licence 3.0. Eventual photos shown in this page may or may not be from Wikipedia, please see the license details for photos in photo by-lines.

Category / Seasonal Status

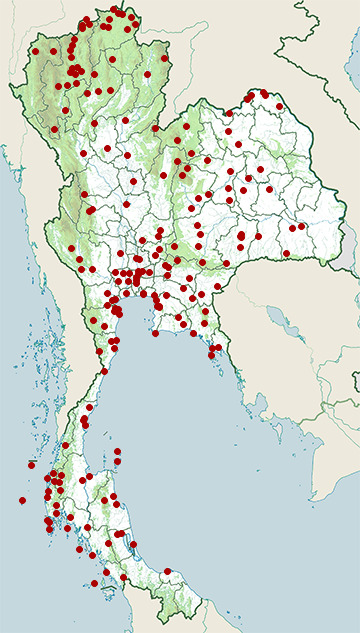

Wiki listed status (concerning Thai population): Very common winter visitor

BCST Category: Recorded in an apparently wild state within the last 50 years

BCST Seasonal statuses:

- Resident or presumed resident

- Non-breeding visitor

Scientific classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Coraciiformes

- Family

- Alcedinidae

- Genus

- Alcedo

- Species

- Alcedo atthis

Common names

- Thai: นกกะเต็นน้อยธรรมดา

Subspecies

Alcedo atthis atthis, Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

Range: Breeds from northwestern Africa and southern Italy east to Afghanistan, Kashmir region, north Xinjiang, and Siberia; it is a winter visitor south to Israel, northeastern Sudan, Yemen, Oman and Pakistan. Compared to A. a. ispida, it has a greener crown, paler underparts and is slightly larger.

Alcedo atthis bengalensis, Johann Friedrich Gmelin, 1788

Range: Breeds in south and east Asia from India to Indonesia, China, Korea, Japan and eastern Mongolia; winters south to Indonesia and the Philippines. It is smaller and brighter than the European races.

Alcedo atthis floresiana, Richard Bowdler Sharpe, 1892

Range: Resident breeder from Bali to Timor. Like A. a. taprobana, but the blues are darker and the ear-patch is rufous with a few blue feathers.

Alcedo atthis hispidoides, René-Primevère Lesso, 1837

Range: Resident breeder from Sulawesi to New Guinea and the islands of the western Pacific Ocean Plumage colours are deeper than in A. a. floresiana, the blue on the hind neck and rump is purple-tinged and the ear-patch is blue.

Alcedo atthis ispida, Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

Range: Breeds from south Norway, Ireland and Spain to western Russia and Romania and winters south to southern Portugal and Iraq.

Alcedo atthis solomonensis, Lionel Walter Rothschild & Ernst Johann Otto Hartert, 1905

Range: Resident breeder in the Solomon Islands east to San Cristobal. The largest Southeast Asian subspecies. It has a blue ear-patch and is more purple-tinged than A. a. hispidoides, with which it interbreeds.

Alcedo atthis taprobana, Otto Kleinschmidt, 1894

Range: Resident breeder in Sri Lanka and southern India. Its upperparts are bright blue, not green-blue; it is the same size as A. a. bengalensis.

Conservation status

Least Concern (IUCN3.1)

Photos

Please help us review the bird photos if wrong ones are used. We can be reached via our contact us page.

Range Map

- Amphawa District, Samut Songkhram

- Ao Phang-Nga National Park

- Aranyaprathet District, Sa Kaeo

- Ban Laem District, Phetchaburi

- Ban Phai District, Khon Kaen

- Ban Sang District, Prachinburi

- Bang Ban District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Bang Len District, Nakhon Pathom

- Bang Pakong District, Chachoengsao

- Bang Phra Non-Hunting Area

- Bang Pu Recreation Centre

- Bangkok Province

- Borabue District, Maha Sarakham

- Bueng Boraped Non-Hunting Area

- Bueng Khong Long Non-Hunting Area

- Chatturat District, Chaiyaphum

- Chiang Dao District, Chiang Mai

- Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary

- Chiang Khong District, Chiang Rai

- Chiang Saen District, Chiang Rai

- Doi Inthanon National Park

- Doi Lang

- Doi Lo District, Chiang Mai

- Doi Pha Hom Pok National Park

- Doi Saket District, Chiang Mai

- Doi Suthep - Pui National Park

- Doi Tao District, Chiang Mai

- Erawan National Park

- Fang District, Chiang Mai

- Hang Chat District, Lampang

- Hat Wanakon National Park

- Huai Chorakhe Mak Reservoir Non-Hunting Area

- Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

- Huai Sala Wildlife Sanctuary

- Huai Talat Reservoir Non-Hunting Area

- Kabin Buri District, Prachinburi

- Kaeng Khoi District, Saraburi

- Kaeng Krachan National Park

- Kamphaeng Saen District, Nakhon Pathom

- Kanthararom District, Sisaket

- Kantharawichai District, Maha Sarakham

- Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Chong

- Khao Khiao - Khao Chomphu Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Khitchakut National Park

- Khao Lak - Lam Ru National Park

- Khao Luang National Park

- Khao Phra - Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Sam Roi Yot National Park

- Khao Soi Dao Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Sok National Park

- Khao Yai National Park

- Khao Yoi District, Phetchaburi

- Khlong Luang District, Pathum Thani

- Khlong Phanom National Park

- Khlong Saeng Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khon San District, Chaiyaphum

- Khuan Khanun District, Phatthalung

- Khun Nan National Park

- Khun Tan District, Chiang Rai

- Khung Kraben Non-Hunting Area

- Khura Buri District, Phang Nga

- Klaeng District, Rayong

- Ko Chang National Park

- Ko Lanta National Park

- Ko Libong

- Ko Phra Thong

- Ko Samui District, Surat Thani

- Kui Buri National Park

- Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani

- Kut Thing Non-Hunting Area

- Laem Ngop District, Trat

- Laem Pak Bia

- Lam Nam Kok National Park

- Lan Sak District, Uthai Thani

- Mae Ai District, Chiang Mai

- Mae Chan District, Chiang Rai

- Mae Mo District, Lampang

- Mae Rim District, Chiang Mai

- Mae Sai District, Chiang Rai

- Mae Taeng District, Chiang Mai

- Mae Wong National Park

- Mu Ko Chumphon National Park

- Mu Ko Phetra National Park

- Mueang Bueng Kan District, Bueng Kan

- Mueang Buriram District, Buriram

- Mueang Chaiyaphum District, Chaiyaphum

- Mueang Chiang Mai District, Chiang Mai

- Mueang Chiang Rai District, Chiang Rai

- Mueang Chonburi District, Chonburi

- Mueang Chumphon District, Chumphon

- Mueang Kalasin District, Kalasin

- Mueang Kanchanaburi District, Kanchanaburi

- Mueang Khon Kaen District, Khon Kaen

- Mueang Krabi District, Krabi

- Mueang Lampang District, Lampang

- Mueang Lamphun District, Lamphun

- Mueang Loei District, Loei

- Mueang Lopburi District, Lopburi

- Mueang Nakhon Nayok District, Nakhon Nayok

- Mueang Nakhon Pathom District, Nakhon Pathom

- Mueang Nakhon Ratchasima District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Mueang Nakhon Si Thammarat District, Nakhon Si Thammarat

- Mueang Nan District, Nan

- Mueang Nong Khai District, Nong Khai

- Mueang Nonthaburi District, Nonthaburi

- Mueang Pan District, Lampang

- Mueang Pathum Thani District, Pathum Thani

- Mueang Pattani District, Pattani

- Mueang Phang Nga District, Phang Nga

- Mueang Phayao District, Phayao

- Mueang Phetchabun District, Phetchabun

- Mueang Phetchaburi District, Phetchaburi

- Mueang Phitsanulok District, Phitsanulok

- Mueang Phuket District, Phuket

- Mueang Ratchaburi District, Ratchaburi

- Mueang Samut Sakhon District, Samut Sakhon

- Mueang Samut Songkhram District, Samut Songkhram

- Mueang Sisaket District, Sisaket

- Mueang Sukhothai District, Sukhothai

- Mueang Suphanburi District, Suphan Buri

- Mueang Surat Thani District, Surat Thani

- Mueang Surin District, Surin

- Mueang Tak District, Tak

- Mueang Trat District, Trat

- Mueang Udon Thani District, Udon Thani

- Mueang Uttaradit District, Uttaradit

- Nam Nao National Park

- Namtok Mae Surin National Park

- Namtok Sam Lan National Park

- Ngao Waterfall National Park

- Non Din Daeng District, Buriram

- Non Thai District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Nong Bong Khai Non-Hunting Area

- Nong Song Hong District, Khon Kaen

- Nong Waeng Non-Hunting Area

- Nong Yai Area Development Project Under Royal Init

- Omkoi Wildlife Sanctuary

- Pa Sak Chonlasit Dam Non-Hunting Area

- Pai District, Mae Hong Son

- Pak Chong District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Pak Khat District, Bueng Kan

- Pak Kret District, Nonthaburi

- Pak Phli District, Nakhon Nayok

- Pak Thale

- Pak Thong Chai District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Pathio District, Chumphon

- Pha Daeng National Park

- Phanat Nikhom District, Chonburi

- Phatthana Nikhom District, Lopburi

- Phi Phi Islands

- Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Phu Khiao Wildlife Sanctuary

- Phu Kradueng District, Loei

- Phu Luang Wildlife Sanctuary

- Phu Suan Sai National Park

- Phu Wiang National Park

- Phunphin District, Surat Thani

- Phutthamonthon District, Nakhon Pathom

- Pran Buri District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Pran Buri Forest Park

- Rattanawapi District, Nong Khai

- Sai Noi District, Nonthaburi

- Sai Yok District, Kanchanaburi

- Samae San Island

- Samut Prakan Province

- San Sai District, Chiang Mai

- Sanam Bin Reservoir Non-Hunting Area

- Sanam Chai Khet District, Chachoengsao

- Sathing Phra District, Songkhla

- Si Racha District, Chonburi

- Si Satchanalai National Park

- Similan Islands

- Sirinat National Park

- Sri Nakarin Dam National Park

- Sri Phang Nga National Park

- Surin Islands

- Takua Pa District, Phang Nga

- Taphan Hin District, Phichit

- Tarutao National Marine Park

- Tha Sala District, Nakhon Si Thammarat

- Tha Yang District, Phetchaburi

- Thalang District, Phuket

- Thale Ban National Park

- Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area

- Than Sadet - Koh Pha-Ngan National Park

- Thanyaburi District, Pathum Thani

- Thap Lan National Park

- Thawat Buri District, Roi Et

- Wang Chan District, Rayong

- Wang Nam Yen District, Sa Kaeo

- Wat Phai Lom & Wat Ampu Wararam Non-Hunting Area

- Wiang Kaen District, Chiang Rai